Submerged Strength: The Hidden Side of Mooring Lines

- Magnus Day

- Aug 1, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 15, 2023

As we set our sights on ordering the perfect mooring lines for our Vanguard, Magnus will guide us through the intricacies of this equipment–unveiling the secrets that make these lines our steadfast companions in the unpredictable realm of the open seas.

So, hoist the anchor, trim the sails, and let's navigate the depths that keep our vessels secure and our seafaring dreams alive!

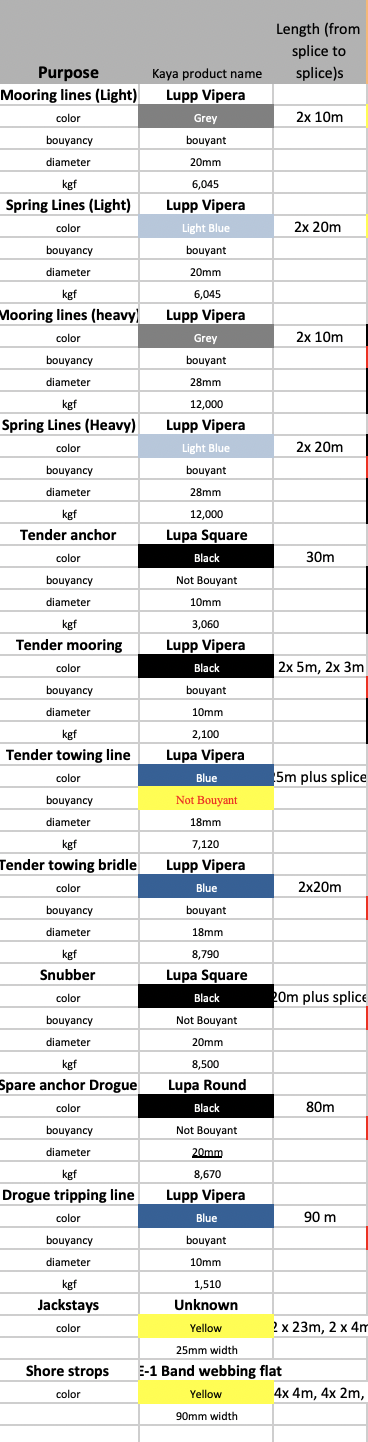

We continue our series of contributions by Magnus Day of Eyos Expeditions. The topic of choice this time is mooring lines, specifically, as we are about to order ours for Vanguard (see enclosed spreadsheet below).

Mooring Gear

"Far too many boats spend their lives in comfortable marinas where lightweight mooring equipment is more than sufficient. As we venture farther afield with fewer facilities and less infrastructure, it’s important to think above and beyond the usual scenarios.

Mooring lines need to be strong, durable, and elastic. To this end, nylon is a good material: plaited construction makes the most of its natural elasticity, and it isn’t prone to a kink in the way twisted three-strand and braid-on-braid can be. Nylon is soft on the hands but can creak horribly as the boat surges back and forth.

From top to bottom. Three strands, 8 plaits, 12 plaits, braid on braid (bottom).

After material, diameter, and construction, breaking strain is the most frequently quoted specification in manufacturers’ brochures. In fact, in cruising boat terms, this figure is almost useless. We are mainly concerned with elasticity (or lack thereof), abrasion resistance, UV resistance, and ‘hand’ or how a line behaves and feels. We should never get anywhere near breaking strain loads, and it is dangerous to do so, as lines with any stretch at all will ping back with potentially deadly consequences. There are several documented cases of workers killed this way.

Polypropylene, while less stretchy, is more durable than nylon and considerably less expensive. It’s also widely available from commercial fishing suppliers and doesn’t seem to creak like nylon.

How many lines?

As a rule of thumb, a vessel should carry two lines about as long as the vessel and four lines half to two-thirds the length. It’s convenient if the longer lines are a different color, so they’re easy to identify.

Another idea is to have two sets of lines: a light set for fair conditions that is easy for the crew to handle and a heavy set for foul weather and when leaving the boat for any period. The two sets can be used in awkward circumstances requiring joining or doubling up on lines.

Although a slightly different subject, let's not forget shore fast lines. For remote locations, these must be long (300 feet plus) and quite strong. You will also need chaffing protection or a metal strop at the shore end to secure to a convenient bolder or tree - see this Blog for more information.

How to configure the lines?

Splicing a loop into the ends is tempting for easy docking, but I would caution against this. It’s all very well where there are handy cleats and bollards to throw the line over, but in many parts of the world, there will be rings or posts, or heaven knows what to tie off to, and a simple whipped end is more versatile. On one notable occasion, we tied off to a phone booth as the only thing available. If a loop is required, the crew can tie a bowline of the requisite size in no time flat.

Rugged, improvised, derelict docks worldwide will often have sharp edges over which mooring lines must be run. Rope manufacturers offer Spectra braided anti-chafe tubes, which is very good, but I usually go to the local fire station and ask for old and out-of-service fire hoses for the same purpose. A small cord tied to each end will hold it in place. A good rub-up with lanolin or silicone grease can work wonders as well.

Used fire hoses are great for preventing chaffing of shore lines.

A fire hose is about as indestructible as it gets. There’s even a company in the UK that turns it into fancy bags.

Mooring fixtures

In general, the mooring bollards of many boats are too small and too few. This is where versatility pays off. More versatility allows for more creativity with your mooring setup, which equals more choice and greater safety in where you and your boat can go.

Ideally, each side of the vessel should have two bollards towards the bow, two midships around the widest part of the hull, and two on the quarter with one on the side and one on the stern. This allows for oddly-shaped docks, rafting up with other yachts, lines ashore, anchor redirects, and combinations thereof. Bollards should be fixed to the outer edge of the deck so they are the first thing the mooring rope touches onboard—fairleads should be unnecessary as they cause chafe.

"H" bollard design, the same configuration is used on all 10 bollards on Vanguard.

Of the many designs, ‘H bollards’ are probably the easiest to use and most versatile. But it’s important to get the proportions correct. I skippered an expedition sailboat called Pelagic Australis for around 70,000 sea miles, and it’s one of many details its designer, Tony Castro, got right. One or more lines are led out through the middle of the bollard so they can’t escape and damage anything with tidal height changes, and it’s easy to lead them to a winch. The 100mm diameter posts allow the crew to surge and snub lines with perfect control when docking and un-docking. On a sailboat, bollards make a great place to rig preventers and barber haulers as well. The design is followed through the whole of Pelagic Yachts’ size range. See the drawing below.

Steve and Linda Dashew’s range of FPBs also takes this subject very seriously. The stanchions for the lifelines on their motorboats are designed to be strong enough to allow them to re-direct mooring lines so you can always get the perfect angle. Great thinking! "

So what are we ordering for our Explorer Yacht?

Also, a part of Magnus's input, the enclosed (rather long) spreadsheet covers the lines we will order for our explorer Yacht Vanguard.

Two sets of dock lines (fair and heavy weather), color-coded with mainly whipped ends rather than splices.

Reusing and Repurposing dock lines

"In practice, dock lines last for years, and here again is a reason to size up. They last longer. There is an advantage to choosing double-braided (braid-on-braid) lines, even when the sheath (also known as the outer, mantle, or cover—whatever you want to call it) is abraded and UV scorched. The inner core is usually in good order and can be used again. We reuse all our lines as they become worn. Covers make excellent fender lines, and the inner core is dead easy to splice into whatever you need—soft shackles, for instance, if it’s a high-tech material. A line is often intact, save for a bit of damage somewhere along its length. In this case, it’s worth cutting the worn part out and keeping the rest for reuse: a shoreline becomes a new dock line, a spring line becomes a stern line, and so on.

Folks often ask how we handle frozen or partially frozen lines. The short answer is: with difficulty. The shorter answer is with gloves.

Frozen lines are horrible to handle, but luckily most of the ice we deal with on lines is sea ice which is relatively soft, kind of like a stiff sorbet. A large rubber mallet and stout boots are worth having—whatever you can muster to beat those lines into submission and get the job done!"

Magnus Day

email : magnus@eyos-expeditions.com

Photo : Magnus and his wife Julia last week in

Tonga trying out a tender they made.